In our previous articles focused on evolution, we talked about the mechanics of evolution. Mix selective pressure, heritable characteristics, and large populations, and you get natural selection. But natural selection can lead to some unusual outcomes.

Why? Natural selection has no intended goal or outcome. While natural selection favors genes that add to a species “fitness,” the definition of “fit” can change. What’s advantageous in one environment may be detrimental in another.

For example, antibiotic resistance is really useful for microbes in hospitals. They are able to survive environments that would otherwise kill them. But there’s a cost to this resistance. The microbes have to spend extra energy to protect themselves. In places where there’s no antibiotic, this puts them at a disadvantage.

Imagine this in a rainforest. Wouldn’t go too well.

There’s another important quirk to evolution. It lacks an “undo” button. For the most part, adaptations are permanent.

For example, all mammals descended from fish species. We know this because fish are vertebrates, just like we are. Yet aquatic mammals, like dolphins or whales, cannot breathe underwater. They still have to breathe air like other mammals.

Who’s really good at holding their breath? YOU ARE!

Because evolution lacks a direction and an undo button, species can end up with body parts that are unnecessary aka vestigial organs. We call these unnecessary body parts “vestigial” because they are the “vestiges” of the past.

Vestigial Organs

Let’s start simple, and work our way up!

Goosebumps

Have you ever wondered why the hair on your neck or arms stands up when you’re scared or cold? It’s because of smooth muscles in your skin called “arrector pili.” These smooth muscles pull your hair follicles to stand up when you feel afraid or cold.

In humans, this is pretty much pointless. Goosebumps don’t warm you up. They also don’t scare any enemies off. So why does this happen?

Scientists think that in our ancestors, this behavior was a good thing. Puffing up your fur makes you look bigger and more intimidating. It also provides a cushion of warm air to help you with the cold. You can see the same reaction in other animals when they puff up. Take cats for instance:

This “puffing up” behavior makes the kitten look bigger than he/she is. This could help a cat escape danger or deter predators. But it in humans it just looks silly.

Tailbone

What is your tailbone useful for? Not much.

A human coccyx (tailbone) serves no purpose. It doesn’t connect to any muscles that we use. It doesn’t transfer signals to other parts of the body. It just sits there, and sometimes causes pain when we sit on it.

But the tailbone, as the name implies, is useful in other animals. Primates who have tails (IE Capuchin monkeys) can use their tails for balance and holding onto objects. Our ancestors likely had tails, so we have the evolutionary remnants of one.

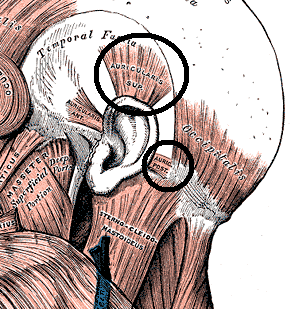

Ear Muscles

Do you know someone that can wiggle their ears? Neat trick, huh? People who can do this are using a group of muscles around the ear to manipulate its shape. There’s no particular purpose to this motion, although it makes a great party trick.

But in other animals (such as cats), these muscles can change the direction that their ears are pointing. Animals that can rotate their ears are better able to detect where a noise is coming from. But this isn’t a problem for humans because we don’t have to worry about predators.

Semi-Vestigial Organs

Semi-vestigial organs aren’t vestigial because they still retain a purpose, but they could have been designed better.

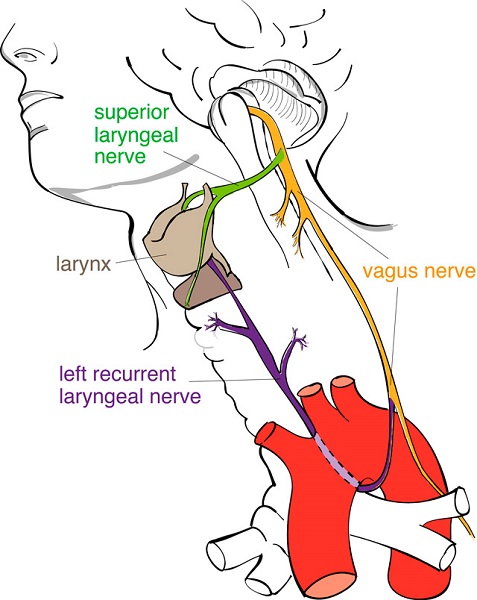

Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve

The Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve (RLN) is a long nerve cell that travels from the brain stem, loops around the aorta, and then passes up to the larynx. It stimulates the vocal cords, allowing you to produce all sorts of different sounds.

Notice how strange that path is? The nerve loops around the aorta for no particular reason. Instead of traveling directly to the larynx, it takes a circuitous route.

In humans, this means the RLN is about ½ of a foot long. Its sister nerve, the superior laryngeal nerve, is only about ¼ of a foot long. In giraffes this nerve can be as long as 15 feet. And in brontosaurus, this nerve was probably 92 feet long.

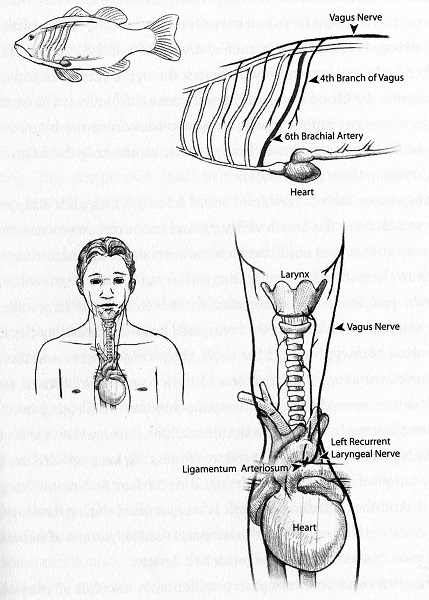

So why is this nerve taking a roundabout route? It’s because this nerve is actually taking a direct path in fish.

But evolution cannot picture the future. As a result, this nerve slowly hooked onto the aorta over time, and hasn’t let go.

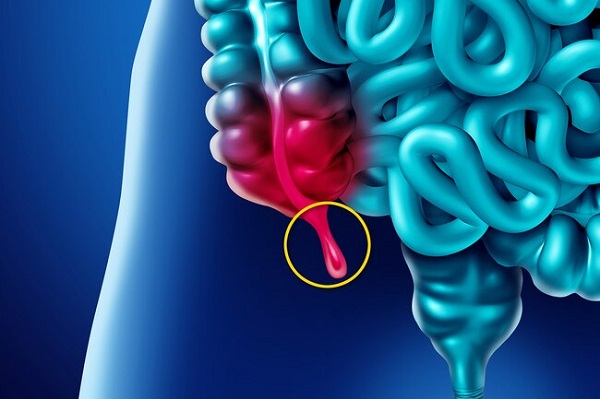

Appendix

The human appendix is a small, worm-shaped organ that connects to your intestines. Its purpose seems to be redundant: it maintains gut bacteria and helps your immune system. It’s not particularly important for either of those purposes. You can remove the appendix and not have to worry about much. In fact, appendectomies are commonplace when people get appendicitis.

In fact, one research paper suggested that the appendix has disappeared and reappeared several times in our evolutionary history. The authors of the study propose that the appendix is useful when sanitation is rare. But it offers almost nothing to modern humans.

Other Animals

Humans aren’t the only ones who hold onto weird vestiges of the past. Other animals have them too.

Whale Hips

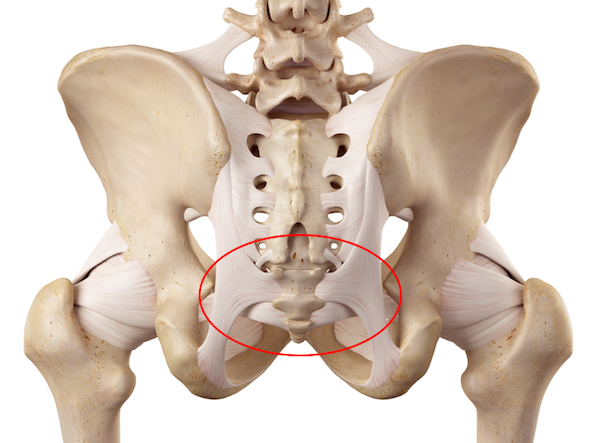

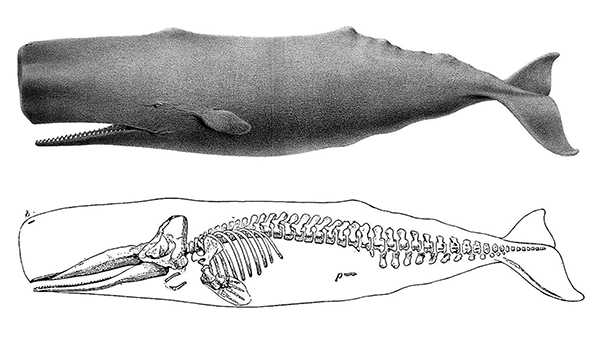

Whales have hips. Not very large hips, mind you, but hips, nonetheless.

Do you see the part labeled “p” on the diagram above? That’s the whale’s pelvis. It’s not connected to the rest of the skeleton at all. It also only serves one purpose -- reproduction.

Wings on Flightless Birds

Flightless birds, such as ostriches or penguins, continue to have wings that aren’t helpful for flight. Despite this, only one group of birds has lost its wings: the New Zealand moas. Modern kiwi birds are similar in appearance, but do have tiny wings.

Hi little guys!

These tiny wings serve no purpose in kiwis. Other flightless birds have seen their wings changed to suit their needs. Penguin wings are now used like dolphin fins, and ostriches use their wings to stabilize themselves while running.

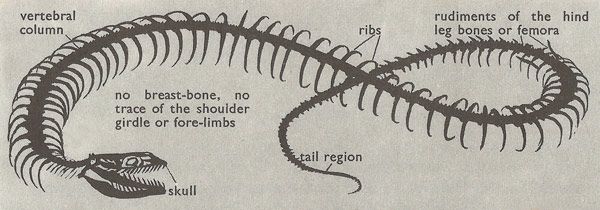

Snake Hips

Boas and pythons actually have the remnants of hip bones and legs. These serve no purpose.

But if you like snake hips… try listening to Snakehips.

Takeaway

So, after learning about vestigial organs, what should you take away from this? After all, it seems like an exercise in pointing out weird things in living creatures. Nature is definitely weird.

Well, the simple fact is that these vestiges of the past are the remnants of evolution. The only way to explain these oddities is to look at the past and see how we got here. We are the result of millions of years of evolution, and evolution is still ongoing.

References:

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4380921/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vestigiality

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Goose_bumps

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arrector_pili_muscle

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coccyx

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23150169

- https://books.google.com/books?id=mTPI_d9fyLAC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=%22laryngeal%20nerve%22&f=false

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1631068312001960?via%3Dihub