First, we should ask the question: What is personalized medicine?

Personalized medicine is exactly what it sounds like. It's medicine that is custom-tailored to you and your needs. It’s also tailored to your neighbor’s needs, as well as your community’s needs. The idea is simple in theory, but in practice it’s much more difficult.

What Makes Personalized Medicine Difficult?

If the idea is so simple and so appealing, why is it so hard to do?

The answer lies in how medical research works. Medical research, like scientific research, requires large sample sizes to determine if a particular medicine is effective. Most of the time, researchers try to randomize the sample participants. This allows them to approximate the general population. But there’s a catch to this. Most of this research targets the general population, not you specifically. So just like one-size-fits-all clothing does not actually fit everyone, many people find that a medication doesn’t work for them.

Might fit some.

There’s also another problem with medical research. Historically, most of the research in medical fields has been conducted on white, upper-class men. Minority groups, women, and the poor were frequently excluded from past medical studies. For example, the word “hysteria” derives from the Greek word for uterus. That’s right, hysteria was only used to refer to female patients. Men were not described as “hysterical.” It wasn’t until Freud that we started to disagree with this notion. However, the process has been slow and difficult.

How Do We Get Around These Problems?

The first and most obvious solution is to improve the diversity of our medical research. If minorities, women, and the poor were excluded from studies, we need to start including them. But this doesn’t solve everything.

Say for instance you’re a researcher studying a blood pressure medication. The medication seems to work, and it passes all statistical metrics needed to get FDA approval. It even passes double-blind, clinical trials, which are the gold standard for research. But for some reason, one small group of people keeps experiencing an unintended side effect. This group appears consistently throughout your tests. As a responsible researcher, you list this as a possible side effect of your medication.

What if it turned out that that small group had something in common, but the commonality wasn’t obvious? If it’s not something like ethnicity, sex, or social class, how do you figure out the common thread?

The answer is artificial intelligence.

Artificial Intelligence: Bringing the Past Into the Present

Unlike humans, artificial intelligence does not carry any preconceived notions about human health outcomes. It doesn’t carry gender norms or biases towards certain groups. Instead, all it does is crunch numbers. It looks at all the information, and then finds relationships between points of data.

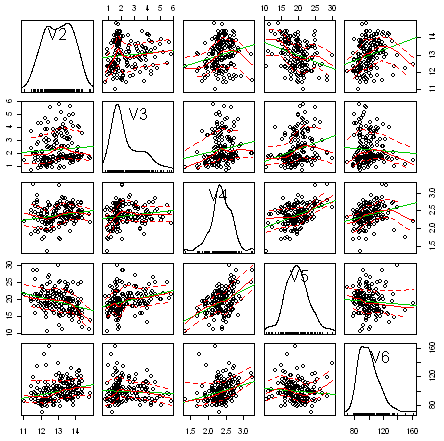

An example of multivariable analysis by AI.

The AI can crosscheck multiple different points of data at the same time. Humans can struggle with this sort of work. If we continue with the blood pressure medication example, we can see how this unfolds. Here are some different data points you might collect from your test subjects:

- Age

- Ethnicity

- Sex

- Systolic Blood Pressure at Rest before medication and after

- Etc, etc, etc.

Artificial intelligence would not only examine age, ethnicity, and sex against different points in time of the study, but also different points in time against each other. But that’s not all AI can do either. More advanced AI, like IBM’s Watson, can pull data from multiple different studies. It can use this data to further advance your research.

This is the fundamental idea behind Genome-Wide Association Studies (or GWAS’s). First, researchers gather a patient’s genetic data and ask them a wide variety of different questions about their medical history. Next, they plop all this information down onto massive spreadsheets. It is then up to the AI to figure out the correlations. What genes correspond to what answers we received?

Research from GWAS have uncovered genes that correspond to how your body might respond to certain medications. If we look at our blood pressure medication, we might find that people with a certain gene variant are more likely to respond negatively to our drug. The linkage to personalized medicine has been revealed. To further explain this, we have a video featuring Dr. Jerome Rotter:

References:

- https://lundquist.org/jerome-i-rotter-md

- https://acmedsci.ac.uk/download?f=file&i=32644

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3480686/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31209850

- https://www.nature.com/articles/d42473-019-00101-y

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23808993.2017.1380516

- https://www.ibm.com/watson/health/business-need/healthcare-research/