Unlike other groups, being “Jewish” can mean different things, depending on who you ask. Some people view it as purely religious, and you are only Jewish if you practice the beliefs. Others see it as an ethnic group. Still others see it as a set of cultural beliefs and values. In this post, we’re going to treat it as all three, which means we will have to mention religious beliefs. We’ll try to remain objective throughout the post.

So let’s explore some of the history that led us to the question of what it means to be Jewish. Can we can come up with a reasonable answer (or answers) along the way?

Important Notes

Before we begin, we should clarify a few things.

Note #1

Jewish people didn’t write their beliefs and traditions down until they encountered the Greeks in 323 BCE. Before then, they maintained a strong tradition of passing stories down orally. As you can imagine, this means that many of the books belonging to the Hebrew Bible were recited by memory. Also, not all oral traditions were recorded in the Hebrew Bible. Some were recorded in the Talmud, which contains additional commentaries, laws, and theology.

While a strong emphasis was placed on perfect recollection, many errors could have passed along this way. People could have later changed names, dates, or details. For example, Exodus describes Egypt enslaving over a million Jewish people. But most historical scholars agree that this was likely not the case.

Historians have had to synthesize these oral traditions, Hebrew Bible, and archaeological evidence. Not all the stories in Genesis and Exodus can be corroborated. This is not to say they are untrue. There are elements of truth woven into the tales.

Note #2

Since their inception, people have been giving the Jews a hard time. In this blog post we will be focusing on the two “primary” diasporas that the Jewish people saw. For the sake of brevity, we are skipping a lot of the smaller diasporas.

But make no mistake, these two “primary” diasporas aren’t the only ones Jewish people have seen. Smaller diasporas stretch from ancient times all the way up to the 20th century. The most recent diasporas were caused by the actions of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Time will tell if there are more diasporas to come.

The Genesis of Judaism

Jewish people originated in the ancient land of Canaan. Their religious beliefs share commonalities with other regional religions. For example, one of Yahweh’s alternate names is “Elohim,” sharing the root “El” with a Canaanite deity. Sometimes the word “ba’al” in Hebrew texts refers to Yahweh, and Baal was a Canaanite deity.

Religious elements from neighboring cultures can also be spotted in the Hebrew Bible. For example, the “Great Flood” story shares similarities with the Sumerian creation myth. It also uses symbolism from the Babylonian deity Marduk who defeated Tiamat (goddess of oceans) with a rainbow. The golden calf in the Ten Commandments story was the Apis bull, a deity in ancient Egyptian beliefs.

If you have the time, try reading about ancient Mesopotamian religions on Wikipedia. It’s a fascinating read.

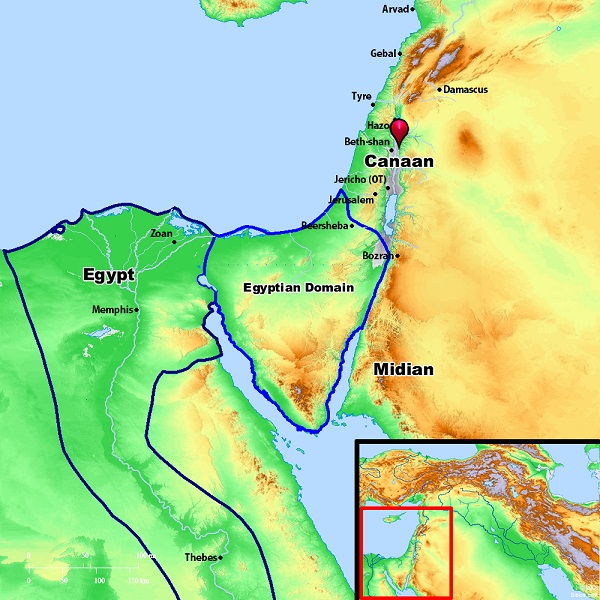

A rough outline of ancient Canaan’s location. Image Courtesy of Bible Map.

According to the Hebrew Bible, the Jewish people started thanks to Abraham. He is the first “Patriarch” of Judaism, and its founding prophet. The story continues that Abraham’s grandson, Jacob had twelve sons. These sons founded the 12 tribes of Judea.

Archaeologists have found it difficult to corroborate these stories, and not for lack of trying. Many of them suspect that these stories are part of a mythology behind the origin of the Jews. Several books have been written on the subject, arguing from both sides.

However, we get our first piece of evidence for the Jews in the form of the Merneptah Stele from Egypt. The Merneptah Stele describes Egypt’s conquest of neighboring regions. One line mentions that “Israel was laid to waste.” This stele has been dated to approximately 1200 BCE. Thus, we have our first non-Biblical evidence for the Jews around 1200 BCE.

At this point, archaeologists and the book of Exodus disagree about what happened next:

- The book of Exodus says that Egypt enslaved all of Israel. It also says that the Jewish people eventually gained their freedom thanks to Moses.

- Archaeologists disagree with this narrative. While the Egyptians did take slaves from the Jews, the Exodus account does not match Egyptian records. The Exodus story also doesn’t fit the geography of the region. Scholars have proposed many alternative explanations, although each one has some issues.

Anyway, the next piece of evidence appears around 1000 BCE, during the Iron Age. Egypt’s pharaoh at the time, Shoshenq I (called Shishak in the Bible), recorded raids on Israel. After that point, the Kingdom of Israel frequently warred with its neighbors. It survived about 400 years until 587 BCE, when it was sacked by Babylon.

The First Diaspora and the Babylonians (587 BCE - 538 BCE)

Around 587 BCE, Babylon sacked the Kingdom of Israel. This caused the first Jewish diaspora, and is called the “Babylonian Exile.” Many Jewish elites were enslaved by Babylon, while commoners fled to neighboring countries. These commoners fled even further after their governor was assassinated. During this time, the tribes lost contact with each other. Some of the captives were able to return to Judea, although others remained in Babylon and abroad.

19th-century engraving depicting the Babylonian exile.

According to the book of Ezra, the Babylonian Exile ended when Cyrus the Great of Persia defeated Babylon in 538 BCE. The Jewish people returned to Judea, and built the Second Temple (the first was destroyed). Babylonian and Persian tablets dated to these times corroborate these stories:

- The Babylonian tablets detail the destruction of the Kingdom of Israel.

- The Cyrus Cylinder describes the “repatriation of exiled peoples.” People believe that this includes the Jews.

The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and Hellenistic Judaism (538 BCE to 110 BCE)

Persia allowed Jewish people to live semi-autonomously. Instead of forcing assimilation, they generally let people live how they wanted. They just had to pay their taxes. Persia maintained this stance until 332 BCE, when they lost to the Macedonians. The Macedonians were led by none other than Alexander the Great.

A mosaic of Alexander the Great on his horse.

Alexander the Great conquered a massive portion of the world. Like the Persians, the Macedonians realized that forcing assimilation was a bad idea. They generally let people live as they wished to, so long as they paid their taxes.

The extent of Alexander the Great’s Empire when he died in 323 BCE. Alexander’s wife was purportedly Indian.

With the Macedonians came Greek culture. This culture encouraged the Jews to collect their stories and write them into books. We now call the collection of these books the Hebrew Bible, or the Tanakh. Evidence suggests that the canonization process took several generations. It ended sometime around the 1st century BCE. Authors wrote the early Tanakh in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek.

However, the Macedonian Empire would not last. The Punic and Macedonian wars led to the downfall of Macedonia and the rise of the Romans. For about 80 years between 140 BCE and 60 BCE, Judea was independent. During this time, Judah was ruled over by the Hasmonean Dynasty.

Want to learn more about the Punic Wars and the impact they had on history? Check out this series of videos by Extra Credits.

The Second Diaspora and the Romans

Rome came along in 63 BCE and defeated the Hasmonean Dynasty. The Roman General, Pompey, laid siege to Jerusalem and captured it after 3 months. After this victory, the Romans installed a former Jewish leader as a puppet. They used him to collect taxes from the new province.

About 70 years later (around 30 CE), tales of a Jewish man from Nazareth started floating around. This man spoke revolutionary things for the time and caused a stir. The Roman prefect of Judea, Pontius Pilate, had him crucified to prevent an uprising. This man, Jesus, started the fledgling religion of Christianity. This upstart religion took many converts from Judaism. But it didn't take off immediately. Christianity wouldn’t become a major religion until Emperor Constantine converted to it on his deathbed in 337 CE.

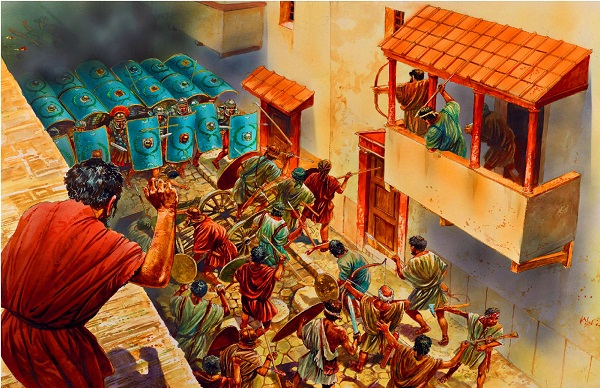

The Jewish people lived peacefully under Roman rule until 66 CE. There was a revolt, leading to the first Jewish-Roman war. This culminated in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Second Temple in 70 CE. After two more rebellions and 70 years, the Roman general Sextus Julius Severus destroyed Judea in the Bar Kokhba Revolt.

Artistic depiction of the Bar Kokhba Revolt. You can probably guess who won.

After this war, Jewish people were removed from Roman-controlled Judea. Rome enslaved or killed those who stayed, and many fled or went into hiding. This was the second great diaspora of the Jewish people. It led to the formation of what we consider modern Jewish groups and ethnicities.

At this point, it is difficult to establish a cohesive narrative. The different groups scattered to the winds. Instead, we’ll switch to examining what it means to be Jewish.

Who is “Jewish”?

For those interested, there is a very long Wikipedia article on this subject. It’s a big source of disagreement in Jewish communities, so our summarization is by no means authoritative.

By Birthright

Traditional Jewish culture discourages young Jewish people from marrying non-Jews (also called Gentiles). Even the Hebrew Bible and the Talmud forbade interfaith marriages:

“ The Gemara asks a question with regard to Rabbi Yoḥanan’s statement. That verse: “Neither shall you make marriages with them” (Deuteronomy 7:3), is written with regard to the seven nations of Canaan. From where do we derive that betrothal does not take effect with the other nations? The Gemara answers: The verse states as a reason for prohibiting intermarriages: “For he will turn away your son from following Me,” which serves to include all those who might turn a child away, no matter from which nation.” -- Kiddushin 68b:6

Before the Greeks and Romans, this prohibition on intermarriage was easy to maintain. Most Jews lived close to one another, and had parents arranging marriages.

But with Greek and Roman rule, this pattern shifted. Fewer marriages were arranged, and many Jews got to choose who they married. This led to an identity crisis. After all, if one of the parents was not Jewish, can you define the child as Jewish? Also, if somebody married into the family, were they Jewish too? And what if somebody stopped believing and became an apostate?

These questions dogged Jewish priests and rabbis. While they didn’t consider interfaith marriages to be valid, they had to consider the children of such marriages. In those cases, they used the example of crossbred species such as horses and donkeys:

Today it would be distasteful to compare interfaith marriages to cross-species hybridization. But this is the standard they settled upon. Thus, they decided that birthright status is determined by the mother, or matrilineally. Even if the child became an apostate, they were still Jewish by birthright. This decision is regarded as true by all current Jewish denominations.

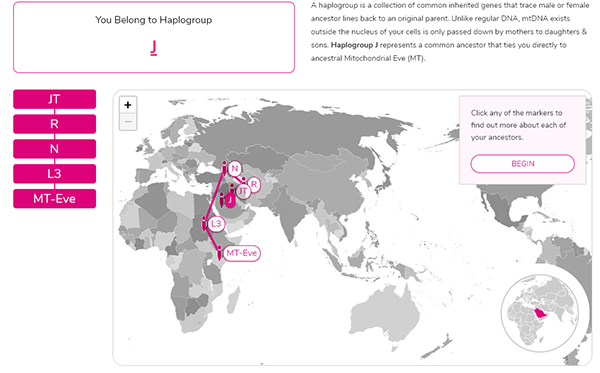

By an amazing stroke of luck, this decision means that mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can determine if you have Jewish ancestry. Mitochondrial DNA can only follow the mother’s line, making it a form of matrilineal descent.

The author of this article has a Jewish mother who claims ancestry back to Israel. These are his mitochondrial DNA test results. CRI Genetics offers mitochondrial DNA testing.

Patrilineal descent is not as well-accepted by the Jewish community. Only some Jewish denominations accept patrilineal birthright status. These denominations are typically more progressive forms of Judaism. More traditional Jewish denominations do not accept patrilineal descent as valid.

By Conversion

Of course, one does not need to be born into Judaism to be Jewish either. Because it is both a religion and ethnicity, a person can convert to Judaism and become Jewish. The process of conversion will differ depending on the denomination of Judaism.

Please note that not all conversions are considered valid by everyone. This will depend on the denomination involved. Traditional Jewish denominations will typically not accept conversions by more progressive Jewish denominations. A few subgroups do not accept conversions at all.

By Similarities in Belief

The rules on birthright descent were determined during Greek and Roman times. But, as illustrated above, diasporas took place before these rules were established. Several Jewish groups split off from the main group before they could accept these rules.

In fact, there is much debate in the Jewish community about the “Ten Lost Tribes.” These tribes were exiled under the Assyrians and Babylonians. The two tribes that survived, Benjamin and Judah, later merged under the banner of “Jews.”

As a result, there are some rare groups out there that practice faiths with remarkable similarity to Judaism. For example, the Lemba people in South Africa follow Jewish practices with distinctly African twists. The Lemba were separated from other Jewish groups for thousands of years but share a similar culture. Hence, several Jewish groups consider them to be Jewish too. However, not all Jewish groups accept this, depending on their religious views. Once again, there is a divide between traditional and progressive Jewish denominations.

Major Jewish Groups (Post-Rome)

Ashkenazi

After the Roman diaspora, a group of Jews went north into what is now Germany. These Jews called themselves the Ashkenazi. They became lighter-skinned like their European neighbors. They also developed a Hebrew-German hybrid language, known as Yiddish.

Ashkenazi people make up the majority of Jews living in Europe and the USA. They also constitute a large number of the Jewish people in Israel.

Many famous people are or were Ashkenazi. Here are just a handful:

- Albert Einstein (scientist and mathematician)

- Leon Trotsky (politician)

- Mila Kunis (actress)

- Jon Stewart (comedian)

- Ruth-Bader Ginsberg (judge and lawyer)

- Gal Gadot (actress and model)

Mizrahi

After the Roman diaspora, a group of Jews went into hiding near the Roman Empire. They stayed near the Middle East, spreading slightly south and east. This group is collectively known as the Mizrahi. The Mizrahi people make up the largest group of Jews living in Israel today.

Many famous people are or were Mizrahi, including:

- Paula Abdul (singer and actress)

- David Hindawi (software designer and businessman)

- Isaac Mizrahi (fashion designer)

- Avshalom Elitzur (physicist and philosopher)

- Gavriil Ilizarov (physician and surgeon)

Sephardi

After the Roman diaspora, a group of Jews traveled along the northern coast of Africa. They ended up on the Iberian peninsula, what is now Spain and Portugal. This wasn't the end of their journey, though. In 1492, Queen Isabella expelled the Jews from Spain. This fractured the Sephardi. Some converted to Catholicism to remain in Spain. Others fled east to the Middle East and rejoined the Mizrahi. Some also joined the Ashkenazi in northern Europe.

The Sephardi make up a large part of the Jewish population in Israel and France. Because they rejoined the Mizrahi and Ashkenazi, it can be difficult to distinguish Sephardic Jews from other groups. Many Ashkenazi or Mizrahi claim Sephardic descent.

Small, But Unusual Jewish Groups

Kaifeng Jews

Some Jewish people went REALLY far east after the Roman diaspora. They ended up in the Henan province of China. These Jewish people are known as the Kaifeng Jews. Their numbers are small, but they still adhere to Judaism. However, the Chinese government is not a fan of them.

Want to learn more about them? Check out this article.

Lemba

The Lemba branched off some time after the Assyrian or Babylonian exile. They traveled far south into Africa. They ended their journey in what are now Zimbabwe and Southern Africa. They continue the practices of abstaining from pork and ritual circumcision. Some Jewish groups do not recognize them as Jewish, while others do.

Want to learn more about them? Check out this article.

Anusim/Marranos/Conversos/Crypto-Jews

In Spain, parts of western Europe, and parts of Africa, Jewish people were forcibly converted to Christianity or Islam. But, many of these Jews continued to practice Judaism in secret. They became known as the Anusim, or “forced ones.”

Want to learn more about them? Check out this article.

Samaritans

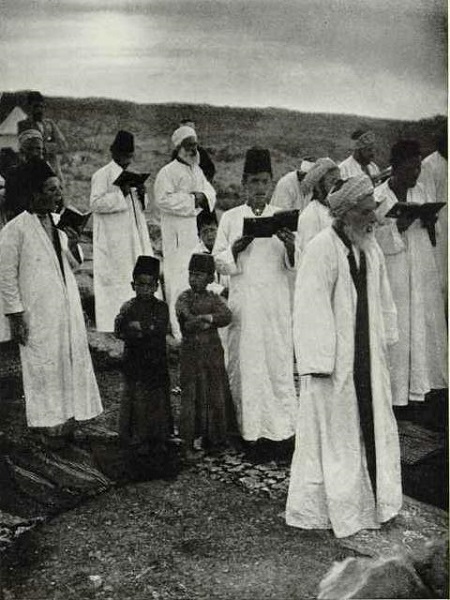

One of the smallest remaining groups of Jews are the Samaritans. Samaritans claim that they are from the lost tribes of Ephraim, Manasseh, and Levi. They currently live in what is now Israel, and their numbers are in the hundreds. When they were exiled, they lost their rabbis and priests. They had to rely on their oral traditions without the guidance of a leading religious figure. The result is a group that has surprisingly ancient views and traditions.

By John D. Whiting - The Last Israelitish Blood Sacrifice by John D. Whiting, The National Geographic Magazine, Jan 1920. Scanned from personal copy., PD-US, Link

Want to learn more about them? Check out this article.

References:

- https://www.jewishdatabank.org/content/upload/bjdb/2018-World_Jewish_Population_(AJYB,_DellaPergola)_DB_Final.pdf

- https://www.webcitation.org/66iJmYkkn?url=http://classes.maxwell.syr.edu/his301-001/jeishh_diaspora_in_greece.htm

- https://www.ancient.eu/Alexander_the_Great/

- https://www.haaretz.com/archaeology/.premium-the-exodus-ancient-semitic-memory-1.5244679

- https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/.premium-were-hebrews-ever-slaves-in-ancient-egypt-yes-1.5429843

- https://www.allaboutarchaeology.org/merneptah-stele-faq.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/El_(deity)

- http://www.touregypt.net/featurestories/sheshonq1.htm

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/babylonian-exile/

- https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/news/lemba-tribe-in-southern-africa-has-jewish-roots-genetic-tests-reveal

- https://www.ancient.eu/article/166/the-cyrus-cylinder/#targetText=The%20Cyrus%20Cylinder%20is%20a,ending%20the%20Neo%2DBabylonian%20empire.

- http://www.historyofmacedonia.org/

- http://www.historyofinformation.com/detail.php?entryid=172#targetText=Circa%20200%20BCE%20%2D%20200,the%20Tanakh%20or%20Hebrew%20Bible%20.

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-hasmonean-dynasty

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Pontius-Pilate

- https://www.britannica.com/event/Siege-of-Jerusalem-70

- https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-bar-kokhba-revolt-132-135-ce

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/intermarriage-and-the-american-jewish-community/

- https://www.sefaria.org/Kiddushin.68b?lang=bi

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Who_is_a_Jew%3F

- https://books.google.com/books?id=vX8moleho2kC

- https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Politics-And-Diplomacy/New-law-says-genetic-test-valid-for-determining-Jewish-status-in-some-cases-506584

- http://www.jewfaq.org/yiddish.htm

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/who-are-mizrahi-jews/

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/sephardic-ashkenazic-mizrahi-jews-jewish-ethnic-diversity/

- https://forward.com/news/349913/who-are-the-kaifeng-jews-and-why-is-china-cracking-down-on-them

- https://www.haaretz.com/zimbabwe-s-black-jews-observe-traditions-if-not-faith-1.5220298

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/crypto-jews/

- https://www.tabletmag.com/jewish-news-and-politics/33879/good-samaritans