“When we know about our ancestors, when we sense them as living and as supporting us, then we feel connected to the genetic life-stream, and we draw strength and nourishment from this.” — Philip Carr-Gomm

Your ancestors entered your life over 50,000 years ago.

They’re still here.

Our ancestors live within us. We carry them in the DNA in every cell in our body.

We may not see or think about them every day, but we are here against all odds because of what our ancestors did to survive.

And while human beings, in their many vast migrations have reached the furthest reaches of the planet, practiced different customs, and found different foods to eat, nearly every culture and religion continues to honor their ancestors. These special celebratory days and times of the year often mark the harvests or the change of seasons.

Most major American holidays celebrate our ancestors by giving thanks for their actions and sacrifices, such as:

- Thanksgiving

- Memorial Day

- Presidents Day

- Veterans Day

- July 4th

If you’re curious about some of the most awe-inspiring ancestor-honoring cultures and what they do—read on!

13 Cultures Around the World that Remember Those Who Came Before Us

Halloween

What began as All Hallows’ Eve, or Hallowe’en, is celebrated on October 31 in the United States, Canada, and the British Isles. Children go door-to-door while wearing costumes, asking for treats, and playing pranks.

The day, and especially the evening of Oct. 31 is celebrated by masquerading, partying, and displaying jack-o'-lanterns, those toothy menacing pumpkins with cut-out faces.

Every October, in preparation for the creepin, crawlin’ Halloween holiday, movie studios release both new and classic scary films, retailers spookify their websites and storefronts, and children can live out their fantasies as Spider-Man and Princess Leia, as they are unleashed upon the sidewalks to seek treats at the doors of neighbors.

But the scariness of the holiday threatens millions of people. Did you know that 7.8% of Americans suffer from Coulrophobia: A Fear of Clowns, and 9.1% suffer severe symptoms, like a deep sense of fear, choking sensations, and dizziness from Samhainophobia: The Fear of Halloween?

Samhain in Scotland

Samhain is an ancient pagan word. Pagan comes from a Latin word paganus, meaning villager, rustic, civilian, and itself comes from a pāgus, which refers to a small unit of land in a rural district.

When Christianity began to dominate the Roman Empire, those who considered themselves Celts did not convert, and instead practiced the old ways in England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. These people came to be known as pagans.

Most people consider Samhain a pagan version of Halloween, but the ancient Celtic holiday of Samhain was originally an important festival marking the end of fall and the beginning of winter. During this time of year, Celts believed the spirits of ancestors could walk among the living at will.

In addition, there was always the chance you could be accosted by fairies, leprechauns, and other mischievous beings who comprised the fae: communities of spirits, the “wee people” and half-dead beings who roamed the fetid swamps and dark forests.

To honor the ancestors and protect oneself from negative fae encounters, celebrants offer food and drink to the ancestors and provide departed family members a seat at the feast. Samhain is still practiced in many areas of Scotland, Ireland, and other locations in the British Isles.

(Want to know even more about Ireland? See our popular blog, Top 5 Irish Ancestry Surprises All Irish Should Know.)

All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day in Europe

All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day are two religious holidays observed in Western Christianity. Celebrated on the first and second days of November following Halloween, these holidays are marked by people remembering and honoring the departed; martyrs, saints, and the souls of faithful Christians.

During these holidays, Christians often visit cemeteries to place flowers and candles on the graves of their loved ones, and many attend church services.

Calan Gaeaf from Wales

The first day of winter in Wales, observed on November 1st, is known as Calan Gaeaf (kalun-gayuf). On this date, people believe that the spirits of the ancestors can walk amongst the living. The Welsh particularly avoid locations like churchyards, crossroads, and cemeteries on November 1st.

The traditional way to honor one’s ancestors on Calan Gaeaf and avoid a negative encounter with the fae spirits or the dead is by dancing around a bonfire. Everyone writes their names on rocks and places them in the flames.

When the fire starts to die out, they immediately run home, believing if they stay, a tailless black sow with a ghostly apparition, a headless woman, "the white lady", will chase them and devour their souls.

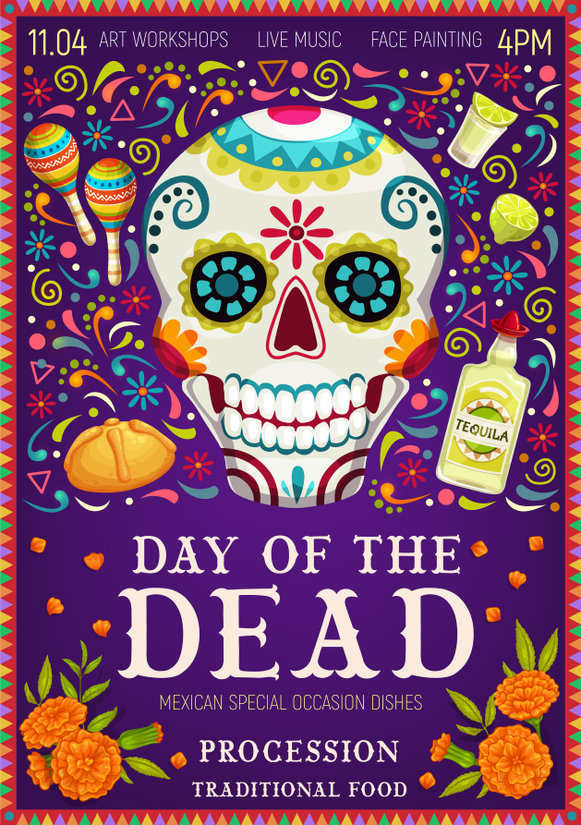

El Día de Los Muertos in Mexico

The Latin American equivalent to All Saint’s Day and All Souls’ Day is El Día de los Muertos, which means “The Day of the Dead.” It’s observed on the first and second days of November.

November 1st is “El Dia de los Inocentes,” or the day of children, also known as All Saints Day, when the souls of children can be reunited with their parents. November 2nd is All Souls Day, or Day of the Dead, where the spirits of adults can come back to visit their families.

Widely celebrated in Mexico, the holiday originated from an ancient Aztec harvest celebration dedicated to the goddess Mictecacihuatl, (mikte-cachi-watil), the “lady of the dead”.

She rules the underworld, and watches over the bones of the dead. The Aztecs believed bones were a source of life in the next world.

The lady of the dead’s grinning skull face, which is seen everywhere during the celebration and in Mexican communities throughout the world, is strongly associated with Dia de Los Muertos. She swallows the stars during the day.

When the Spaniards came to Mexico and introduced Catholicism to the indigenous people, they blended traditional Aztec worship of Mictecacihuatl with Christian beliefs, thus creating Dia de Los Muertos and All Saints Day.

For the “Day of the Dead” festival, celebrants use altars and unique Día de Los Muertos symbology to connect with departed ancestors and family members. During these lively festivities, families and friends visit gravesites, celebrate with calavera skulls decorated in floral patterns, marigold flowers and music, and pray for those who have died.

Mourning, or any signs of sadness, would potentially offend the departed, so El Dia de los Muertos can be seen as a celebration of life for those who have died. The day includes much food and drink, such as tequila with maracas, as well as partaking in specific activities that the dead enjoyed in life.

According to ancient Mexican and Spanish Catholic tradition, those observing Day of the Dead made offerings to deceased ancestors to help their departed souls through their journey to the afterlife. For example, leaving water and tequila on the altar can help quench the spirit’s thirst, and an offering of bread and fruit helps keep the spirit satiated on its trip.

Pchum Ben

In Cambodia, one of the most important festivals in Khmer culture is Pchum Ben (shum-ben). Celebrated each year in mid-September and mid-October and lasting fifteen days, many Cambodians pay respects to their deceased relatives of up to seven generations.

Cambodians gather to fill their pagodas with enormous feasts and food and drink offerings to ease their deceased’s sufferings. Many Cambodians believe that they must visit seven different pagodas to offer food to the monks and pray to their ancestors to receive protection and blessings at home.

Famadihana

In Madagascar, Famadihana (Turning of the Bones) is perhaps, to outsiders, one of the most unusual celebrations for the dead.

During Famadihana, Malagasy people remove corpses from their graves or family crypts and spray them with perfume or drench them in wine. After that, they wrap them up again in silk and fresh cloth and carry them around the tomb with music and songs. They rewrite their names on the cloth so they will always be remembered.

This unique tradition comes from the belief that until a body is fully decomposed, spirits of the dead can come and go between their world and ours. As such, the ritual is performed every seven years.

While the tradition has declined in recent years, the celebration is one of the few occasions for entire families to come together.

Obon Festival

For over 500 years in Japan, the Obon Festival, celebrated in August and early September each year, was established to commemorate deceased ancestors.

Lasting over three days, this Buddhist-Confucian tradition often includes hanging lanterns and lights, feasts with fireworks, games, and dances, including the Obon Odori, a dance performed to welcome the spirits of the dead.

Obon has evolved into a family reunion holiday during which people return to ancestral family sites, visit and clean their ancestors' graves at a time when the spirits of ancestors are supposed to revisit the household altars.

The Hungry Ghost Festival in China

Ancestor worship practice participants make up over 70 percent of the adult population in China and in other East Asian countries. During Hungry Ghost Festival, the deceased are believed to visit the living.

The Hungry Ghost Festival is celebrated on the fifteenth night of the seventh lunar month (the ‘Ghost Month’) in the Chinese calendar. During this time, spirits and ghosts are believed to leave the underworld and wander the world of the living. As such, this is a time to alleviate the sufferings of the dead.

The festivities last an entire month. At the end of the festival, people light flower-shaped water lanterns and place them on lakes or rivers to lead spirits back to the lower realms.

This is not the only time in Chinese culture to celebrate the dead, however. Qingming, also known as Ancestors Day or Tomb-Sweeping Day, is celebrated in early April, marking a time when families visit the tombs of their ancestors to clean them.

The ritual includes making papier-mâché forms of material items such as clothes, gold, and other fine goods for the visiting spirits of the ancestors. There is burning of incense, offerings of food and tea, as well as offerings of money and joss paper (sheets of paper that are burned during traditional Chinese ceremonies that honor the deities or ancestors).

Other festivities include buying and releasing miniature paper boats and lanterns on water, which signify giving directions to the lost ghosts and spirits of the ancestors and other deities.

Ari Moyang in Malaysia

Once a year, the Mah Meri tribe of Selangor, an aboriginal ethnic group on Carey Island (an island roughly 140km/90mi from the Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur) celebrates Ari Moyang, otherwise known as Ancestor’s Day.

This celebration is all about giving thanks to the spirits for all the good things that have been bestowed upon the villagers. On Ancestor’s Day, locals don beautiful, intricate costumes and masks, and offer prayers and blessings to their forefathers, thanking them for good fortune, and asking them for prosperity in the future.

Ari Moyang is celebrated by the native people offering prayers, especially to Moyang Gadeng, their female spirit guardian. Those of the Mah Meri tribe are skillful with craft work, and their exceptional weaving skills are showcased in their handcrafted skirts, colorful headbands, and sashes worn during the celebration.

Paganito in the Philippines

According to an ancient Filipino religion, spirits called Anito inhabit every part of the world. The Anito are the spirits of the ancestors, and they influence events in the lives of the living.

The Paganito ceremony (there’s that word, “pagan” again!) is a type of spiritual seance, in which a traditional shaman communicates with these Anito spirits. The term Anito is also sometimes used to refer to acts of worship and sacrifices used to please the ancestral spirits.

The Paganito is an offering dedicated to the divine Diwata and one’s ancestors.

The ritual consists of drinking pangasi, a fermented rice beverage that is a ceremonial drink in all rituals and feasts, as well as a sacrifice of the tinorlok, or hog that is killed during their ritual dance, the taruk. Singing, chanting, and feasting make up this colorful celebration of the Paganito ceremony.

Chuseok in Korea

One of Korea’s biggest holidays outside of Lunar New Year, Chuseok is a major celebration time in both North and South Korea, and is like the American holiday of Thanksgiving in many ways. It’s a harvest festival, celebrating a bountiful autumn season.

However, Chuseok is specifically dedicated to thanking the ancestors for a plentiful harvest. A ritual called charye takes center stage during Chuseok, involving laying out food and lighting incense for departed relatives.

Seongmyo is a family visit to the ancestral graves, which is usually accompanied by beolcho, a cleaning of the graves of their ancestors as a way of saying thanks.

On Chuseok, Koreans visit their ancestral hometowns to share a feast of traditional foods such as songpyeon, a rice cake stuffed with a yummy mix of sesame seeds, black beans, mung beans, cinnamon, pine nut, walnut, chestnut, jujube, and honey.

Family shares hangwa, artistic food decorated with natural colors and textured with patterns. They also partake in rice wines such as sindoju and dongdongju.

Some believe that if a single woman makes a pretty songpyeon, she will find a great husband, and if a pregnant woman makes a pretty songpyeon, she will have a pretty daughter.

Pitru Paksha in India

A Hindu tradition lasting fifteen days during the month of Ashwin, Pitru Paksha (Fortnight of the Ancestors) marks a remembrance of one’s ancestors, particularly through food offerings.

Hindu myth describes a deceased warrior who couldn’t find any food in heaven because he had never honored his ancestors with food offerings. As this was not a good thing for a son to do, the festival includes ceremonies and rituals performed so that departed souls can attain peace.

In the Hindu religion, the Sraddha ceremony is a serious religious and social responsibility. All male members of the Hindu faith, apart from some holy men known as sannyasis, are required to take part in the ritual.

Sraddha is performed for deceased parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. It’s thought to protect, support, and nourish the spirits as they travel through the afterlife and to eventual reincarnation.

To perform Sraddha rites, a male family member, known as the Karta, makes offerings to local priests and to the souls of the deceased directly. The offerings generally consist of nourishing rice balls called pinda pradaana.

The Karta often performs services for the priests or Brahmanas as well, including feet-washing and other acts of devotion.

How Can I Discover Who My Ancestors Were?

Ancestor worship plays a role in nearly every religion and culture around the world. Throughout human history, we’ve dealt with death partly by continuing to communicate with the ones we’ve lost.

In some cultures, communication with the departed evolved to include elaborate grief rituals, ancestral traditions, and worship.

Ancestor worship is any religious practice based on the belief that deceased family members continue to exist in some capacity. Often, that includes a belief that the spirits or souls of the deceased have an impact on the lives and destiny of the living.

Knowing one’s heritage and ancestors can make us feel connected. Many support the notion that being connected to our loved ones, such as ancestors, our parents, and our community, boosts our mental health and happiness.

Do you know the rituals that your ancestors practiced? What your ancestors did is a part of you, and now you have a way to see into that past through ancestry genetic testing.

If you want to know how far back a DNA kit can go to discover your own ancestors, read our blog entitled, “How Many Generations Can A DNA Test Trace My Ancestry?”

CRI has one of the industry’s best ancestry products going back up to 50 generations.

Whether you offer up prayers or clean the graves of your ancestors, one thing is sure: your journey continues. Somewhere, somehow, those who came before us are honoring us now as we take each precious breath.

They lived, and that is an awe-inspiring feat that we can celebrate every day.

For more in-depth information on creative pathways to discover your ancestors, read our new blog “Y-DNA and Tracing Your Father’s Ancestry: A Woman’s Guide to Paternal Lineage.”

Resources:

www.joincake.com

www.theculturetrip.com

www.handandland.com

www.latitudes.nu

https://diwatahan.tumblr.com/

https://walkwithsandra.blogspot.com/

www.wikipedia.com